Battle of Kiev (1941)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

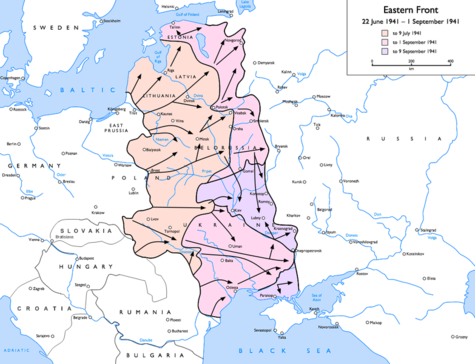

The Battle of Kiev was the German name for the operation that resulted in a very large encirclement of Soviet troops in the vicinity of Kiev during World War II. It is considered the largest encirclement of troops in history. The operation continued from 23 August-26 September 1941 as part of Operation Barbarossa.[1] In Soviet military history it is referred to as the Kiev Defensive Operation (Киевская оборонительная операция), with somewhat different dating of 7 July-26 September 1941.

Nearly the entire Southwestern Front of the Red Army was encircled with the Germans claiming 665,000 captured. However, the Kiev encirclement was not complete, and small groups of Red Army troops managed to escape the cauldron days after the German pincers met east of the city, including head quarters of Marshall Semyon Budyonny, Marshall Semyon Timoshenko and Commissar Nikita Khrushchev. The commander of the Southwestern Front, Mikhail Kirponos, was trapped behind enemy lines and killed while trying to break through[2]. The Kiev disaster was an unprecedented defeat for the Red Army, exceeding even the Minsk tragedy of June-July 1941. On 1 September, the Southwestern Front numbered 752-760,000 troops (850,000 including reserves and rear service organs), 3,923 guns & mortars, 114 tanks and 167 combat aircraft.

The encirclement trapped 452,700 troops, 2,642 guns & mortars and 64 tanks, of which scarcely 15,000 escaped from the encirclement by 2 October. Overall, the Southwestern Front suffered 700,544 casualties, including 616,304 killed, captured, or missing during the month-long Battle for Kiev. As a result, four Soviet field armies (5th, 37th, 26th, & 21st) consisting of 43 divisions virtually ceased to exist. The 40th Army was badly affected as well. Like the Western Front before it, the Southwestern Front had to be recreated almost from scratch.[3]

Contents |

Prelude

After the quick initial success of the Wehrmacht, especially in the Northern and Central sector of the Eastern front, a huge bulge in the south remained, where a substantial Soviet force, consisting of nearly the entire Southwestern Front was located. In the Battle of Uman a significant victory over the Soviet forces was achieved, but the bulk of forces under Semyon Budyonny's command were still concentrated in and around Kiev. While lacking mobility and armor, due to the majority of his armoured forces lost at the Battle of Uman, they nonetheless posed a significant threat to the German advance and were the largest single concentration of Soviet troops on the Eastern Front at that time.

At the end of August, the German Army High Command (Oberkommando des Heeres, or OKH) had the option of either continuing the advance on Moscow, or destroying the Soviet forces in the south. Because the German Army Group South (Heeresgruppe Süd) lacked sufficient strength to encircle and destroy the forces, a significant contribution from Army Group Center (Heeresgruppe Mitte) was needed to accomplish the task. After a dispute within the German High Command, the bulk of Panzergruppe 2 and the 2nd Army were detached from Army Group Center and sent due south to encircle the Soviet army and meet the advancing Army Group South east of Kiev.

The battle

The Panzer armies progressed rapidly to conclude the encirclement, a move that caught Budyonny by surprise. He was therefore relieved by Stalin's order of 13 September. No successor was named, leaving the troops to their individual corps and division commanders. The encirclement of Soviet forces in Kiev was achieved on 16 September, when Kleist's 1st Panzer Army and Guderian's 24th Corps met at Lokhvitsa, 120 mi (190 km) behind Kiev.

After that, the fate of the encircled armies was sealed. For the Soviets, a disaster of staggering dimensions now unfolded. With no mobile forces or supreme commander left, there was no possibility to break out from the encirclement. The German 17th Army and 6th Army of Army Group South, as well as the 2nd Army of Army Group Center subsequently reduced the pocket, aided by the two Panzer armies. The encircled Soviet armies at Kiev did not give up easily. A savage battle in which the Soviets were bombarded by artillery, tanks and aircraft had to be fought before the pocket was reduced. By 19 September, Kiev had fallen, but the encirclement battle continued. In the end, after 10 days of heavy fighting the last remnants of troops east of Kiev surrendered on 26 September. The Germans claimed 600,000 Red Army soldiers captured, although these claims have included a large number of civilians suspected of evading capture. Hitler called it the greatest battle in history.

After the Battle

By virtue of Guderian’s southward turn, the Wehrmacht destroyed the entire Southwestern Front east of Kiev during September, inflicting 600,000 losses on the Red Army, while Soviet forces west of Moscow conducted a futile and costly offensive against German forces around Smolensk. After this Kiev diversion, Hitler launched Operation Typhoon in October, only to see his offensive falter at the gates of Moscow in early December. Some claim that had Hitler launched Operation Typhoon in September rather than October, the Wehrmacht would have avoided the terrible weather conditions and reached and captured Moscow before the onset of winter.

This argument too does not hold up to close scrutiny. Had Hitler launched Operation Typhoon in September, Army Group Center would have had to penetrate deep Soviet defenses manned by a force that had not squandered its strength in fruitless offensives against German positions east of Smolensk. Furthermore, Army Group Center would have launched its offensive with a force of more than 600,000 men threatening its ever-extending right flank and, in the best reckoning, would have reached the gates of Moscow after mid-October just as the fall rainy season was beginning.

Finally, the Stavka saved Moscow by raising and fielding 10 reserve armies that took part in the final defense of the city, the December 1941 counterstrokes, and the January 1942 counteroffensive. These armies would have gone into action regardless of when Hitler launched Operation Typhoon. While they effectively halted and drove back the German offensive short of Moscow as the operation actually developed, they would also have been available to do so had the Germans attacked Moscow a month earlier. Furthermore, if the latter were the case, they would have been able to operate in conjunction with the 600,000 plus force of Army Group Center’s overextended right flank.

Glantz, David M., Forgotten Battles of the German-Soviet War (1941-1945), volume I: The Summer-Fall Campaign (22 June-4 December 1941). Carlisle, PA: Selfpublished, 1999.

Glantz, David M., Forgotten Battles of the German-Soviet War (1941-1945), volume II: The Winter Campaign (5 December 1941-April 1942). Carlisle, PA: Selfpublished, 1999.

References

- ↑ The Devil's Disciples: Hitler's Inner Circle, Anthony Read, p. 731

- ↑ http://gpw.tellur.ru/page.html?r=commanders&s=kirponos

- ↑ Erickson, The Road to Stalingrad, 1975

- John Erickson, The Road to Stalingrad

See also

- Battle of Uman

- Battle of Bialystok-Minsk

- Battle of Kiev (1943)

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||